This wide- and large- screen layout

may not work quite right without Javascript.

Maybe enable Javascript, then try again.

Grandma Dover's Autobiography

My great-grandmother (my father's mother's mother) wrote her reminiscences

when she was about 90.

They're interesting not because they document unusual people

but rather because they're a first-hand account by a woman

of what her life was like

in a period that seems the distant past to most of us.

For her, "pioneering" and "homesteading" in the west

were the real life she lived,

not something she read about in a book.

of what her life was like

in a period that seems the distant past to most of us.

For her, "pioneering" and "homesteading" in the west

were the real life she lived,

not something she read about in a book.

Her reminiscences have quite a few typographical questions, some due to her unique spellings, some from transcribing her longhand, some because the typist was in a hurry, and a few more introduced by my OCR process transcribing her document to the web. Because it's not clear which errors came from where, I've not tried to "fix" any of them except my own. I've tried simply to present her historical document verbatim -- if you find OCR errors, please let me know.

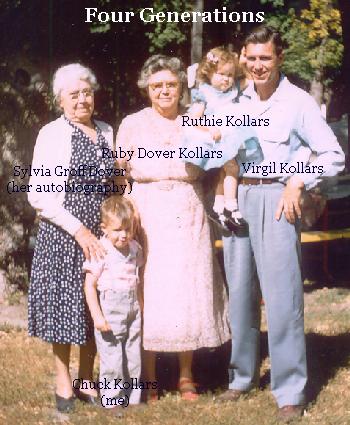

Late in her life this photo was taken with her, her daughter (my grandmother), her grandson (my father), me and my sister.

For reference, facsimile images of the original typed and printed manuscript pages are here too -- click on the little pictures of pages at the right throughout this document.

There's lots of history and genealogy on the web. You may for example be interested by this Kollars family tree. Or as an example of what's available elsewhere on the web, see the Madison County Nebraska portion of a genealogy project (Grandma Dover lived in Madison, Nebraska for many years).

A Brief Autobiography of Sylvia M. Dover

Autobiography of Sylvia Groff Dover

(Written 1957-1959)

My parents were both born in Frederick County, Maryland. Father, Golden B. Groff, was born March 9, 1841 in Eylers Valley, Frederick County, Maryland. Mother, Catherine Josephine E. Stultz, was born March 25, 1844 in Frederick County, Maryland. Both grew up there, and they were married there August 26, 1862. In 1865 they moved from Maryland to Dubuque, Iowa. After living at Dubuque for four or five years, they came to Nebraska and took up a homestead in Cedar County, Nebraska. To this union eight children were born:

- Milton Elsworth Groff born June 20, 1863 near Frederick Mills, Frederick County, Maryland.

- Amanda C. D. Groff born January 13, 1865 near Frederick Mills, Frederick County, Maryland.

- Dolabell Groff born October 28, 1866 near Cascade, Iowa.

- Sylvia May Groff born September 7, 1869 in Black Hawk County, Iowa.

- Bertha Alice Groff born November 12, 1872 in Dixon County, Nebraska.

- Arthur Proctor Groff born January 12, 1877 in Benton County, Iowa.

- Lulu Maud Groff was born April 26, 1880 in Cedar County, Nebraska.

- Frederick Lincoln Groff born October 3, 1883 in Cedar County, Nebraska.

I came with my parents from Iowa to Nebraska in a covered wagon in 1870 before I was a year old. My earliest recollection is of living in a dugout on a homestead in Cedar County, Nebraska, on Logan Creek, about a mile from where the town of Laurel is now located.

Mother said their nearest neighbor, when they moved there, was a bachelor who lived ten miles from them, and that she didn't see a single white woman the first six months they lived there.

The first family I remember were the Fred Bakers. They took up a homestead joining ours. Later James Duncans settled on a place about two or three miles from us. I remember them well.

The folks got sister Amanda and I a china doll for Christmas, when I was a little more than five years old. My doll had its hair parted on the side like a boy--girls wore their hair parted in the middle those days. Mother asked Mrs. Duncan to dress the dolls, and Mrs. Duncan thought it would be fun to put whiskers on mine. She cut a little snip off a buffalo robe and pasted it on the doll's chin. When they gave it to me, I cried and threw the doll on the bed, and would not touch it until they took the whiskers off. I still have the head of that doll. We did not have many toys in those days--we would not have had the dolls if they had cost as much as dolls cost now. They were china heads. People bought the heads and made bodies, and clothes for them. I remember having one doll before that one, but I cannot remember having any other toys during those first six years of my life.

While we were homesteading, money was very scarce, so, of course, food, and clothing came first. We always had enough to eat though our food was very plain--no fancy desserts--or desserts of any kind for that matter. Sometimes we had some ginger bread, cookies, or sometimes a pumpkin pie--that was about the extent of it. We used to have corn bread quite often, and we used frying grease and molasses a great deal in place of butter.

Of course, I was too young to remember what they did the first year we lived on the homestead, but Mother said they plowed up a weed patch down by the creek, and she raised a good garden there. I have heard her say that she had beets so large that two would not fit in a kettle at once.

They broke up prairie, and raised some sod corn. Then there were lots of prairie chickens, wild ducks, deer, also some antelope, and once in a while, an elk. There were no restrictions on how many you killed or when. There was plenty of fish in the creek, and you could fish any time you wanted to, and get as many as you could catch. There was lots of rabbits, too, so we got by pretty well for food.

Our clothes--what we had--were just as plain as our food. Mother made all our clothes by hand, and knit our stockings, too, until we were old enough to knit them ourselves. We were not very old when we learned to knit. There were five of us children in addition to her and Father to sew for, and before she got a sewing machine she had to make underwear and all by hand.

I do not remember that she ever did have a washing machine. She made lye by putting ashes in a barrel, poured water on the, letting it seap out through a hole close to the bottom of the barrel. She used that along with cracklings and any waste grease she might have to make soap. It was brown, soft, slimy stuff, but it got the dirt out.

In the dugout we had our beds--one was made of two by fours nailed together for the frame and legs, with slats laid across it to put the straw tick on. We also had a table, some chairs, a cook stove, some dishes, pots, and pans. That was our furniture.

Sometimes we only had a grease lift--if we ran out of oil or candles, and could not get to town to get oil. A grease light was made by rolling up a piece of cloth until it was about the size of your finger, tying it to keep it from unrolling, and soaking it in grease. Then you would stand it up in a saucer with some grease in it, and light it like a candle. It did not make a very good light, but it was better than none.

There were four of us children then, my second sister having died the winter before we moved out there. She was four years old or a little more when she died, so, of course, I do not remember her at all.

We had no one to play with but ourselves, but I think we were just as happy and maybe more so than most children are now. We never saw anything different, so did not know anything different.

The folks spent three or four months of several winters down at Ponca landing, and Father cut cord wood to earn a little extra money. That is where Alice was born, and where I fell on a sharp ax and cut myself. They were allowed to leave the claim a certain length of time each year. No one could jump their claim if they did not stay away longer than the time allowed.

When Father had to go to town to get supplies it always took two days or more to make the trip with a team and farm wagon. There were no roads, and it was slow going. They had to drive stakes, and pick out land marks of some kind across the prairie at first, to know how to get to town and back again. Father used to bring each of us a stick of candy when he went to town, and that was a big treat to us.

Father had an accordion, and he often played it for a while in the evening which we enjoyed. We had no doctor nearer than twenty-five miles, and no way to get one except to drive that distance to get him. So Father did the doctoring in our family. He had an old doctor book, three kinds of powder, and some pills. If any of us did not feel well, he gave us whichever kind of powder or pill that he thought we needed. If we had a fever they stood us in a tub, wrapped a sheet around us, and poured cold water over us. I remember getting a cold sheet pack once.

One night about dark, two Indians came and wanted to stay all night. The folks did not like to let them in, but they did not like to turn them away either. It was a cold night, so Father told them that if they would give him their guns and knives for the night, they could stay. They gave Father their guns and knives, and came into the house. Mother gave them some supper and made them a bed on the floor. In the morning, they took their guns and knives, and went on their way.

One morning, at a later time, an Indian came and wanted to borrow a spade to dig some peat. He said he would bring the spade back at sundown. There happened to be someone there that morning, and he told the folks that was the last they would ever see of their spade. Mother said just about sundown the Indian came back with the spade, and a big plate of venison. The folks always got along well with the Indians who were always friendly toward us.

One night about three hundred Indians camped just a little way back of

our place. Then another time a lot of them camped about four or five miles up

the valley from us. One afternoon we all went up to the camp, went into one

![]() tepee, and sat on the ground around the campfire with them. They had a big

long-stemmed pipe which one would take a few puffs of, and then pass it to the

next one. As none of our family smoked, they did not take a puff. They had

a lot of muskrat tails skinned, and laid on a kind of rack which they had

fixed rather high above the fire to smoke and dry them. Then we went into

another tepee, and there was a squaw frying doughnuts over the campfire. It

was in the fall, and they were hunting and trapping.

tepee, and sat on the ground around the campfire with them. They had a big

long-stemmed pipe which one would take a few puffs of, and then pass it to the

next one. As none of our family smoked, they did not take a puff. They had

a lot of muskrat tails skinned, and laid on a kind of rack which they had

fixed rather high above the fire to smoke and dry them. Then we went into

another tepee, and there was a squaw frying doughnuts over the campfire. It

was in the fall, and they were hunting and trapping.

Father used to raise some broom corn, and make brooms to sell. I think it was $2.50 a dozen which he got for them. That helped some, for a dollar went a good deal farther then than it does now. I remember so well, him sitting there in the dugout on that old bench with the vise, making brooms in the winter. I have the knife, and Maud has the needles he used to make them.

They had broken more ground, and were raising more crops when along came the grasshoppers. The ground and sky just seemed to be full of them. I remember going outdoors and they flew into my face and all over me every step I took. They stayed about three days, ate just about everything, then rose up like a flock of birds, and flew on to greener pastures, leaving very little behind for anyone. Father had a field of wheat that was just ready to cut, so he went out and cut it to save enough to make our flour.

One think they always had to look out for in the fall was prairie fires. When one got started in that tall heavy grass, there was really a prairie fire. The flames would leap way into the air. They had to make fire guards every fall and they had to be quite wide to keep the fire from jumping them. They made the guards by breaking several furrows back a way from the place, then burning the grass off between that and the place. It was not only along the creek in the tall grass that the fire hazard was great, but though the grass was shorter farther back, it was quite thick and heavy all over, and there could be a good big fire any place it got started.

The prairie fires I remember, and the visit to the Indian camp were after we came back from Iowa. I do not remember anything about prairie fires before that. I guess there was no one to start one before that except Duncans, the Bakers, and us. The Indians must have been careful about fires. They would not want to drive the wild game out of the country.

Our nearest postoffice was Ponca; and the nearest railroad was Sioux City. These are a few of the things I remember during the first six years of my life.

As soon as Father proved up on the homestead, they loaded our few belongings into the covered wagon, we all climbed in, and moved back to Iowa. The first year we lived between Newton and Marshalltown near a place called Laurel. It was while we lived there that we children first started to school. Milton was about twelve years old then. I did not want to go to school, and I got spanked nearly every morning to make me go, then spanked again in the evening for crying while I was there.

The next year we moved to Benton County near Shellsburg. Father rented a place there and along with other crops, raised some broom corn and sold a load at the blind asylum. It might be interesting to tell you how they harvested the broom corn. When it was ready to cut, they went along between every two rows and broke the stalks over criss-cross at a convenient height to cut them. That left the heads at the outside of every two rows. Then they went along and cut the heads with a knife. They took them in, and put them on racks made of posts and poles, one shelf above another, to dry. After they were dry, the seeds had to be cleaned off the brush, then it was ready to make into a broom.

As I remember, Vinton was the town where the asylum was located. We all went along and visited the asylum to see the work which the blind people did. They did a lot of different kinds of work, but the things I remember most were their sewing and bead work. The folks got each of us children a piece of the bead work as they made it to sell. I still have my piece, which is a little beaded basket.

It was in Shellsburg that we children first saw a Christmas tree. It was a beautiful big tree in the church. Milton was thirteen years old then.

As nearly as I can remember, we were in Iowa about two and a half years.

The folks were not satisfied in Iowa paying rent and having their own land idle.

![]() So once again they loaded up the wagon, we all climbed in, and started back

to Nebraska. I remember crossing the Missouri River--we came part way across

on a ferry boat, and the rest of the way oh a pontoon bridge. We came back

in the fall and lived in Ponca that winter.

So once again they loaded up the wagon, we all climbed in, and started back

to Nebraska. I remember crossing the Missouri River--we came part way across

on a ferry boat, and the rest of the way oh a pontoon bridge. We came back

in the fall and lived in Ponca that winter.

In the spring we moved to a farm about two miles from our place. The Bakers had moved away, so the next year we moved into a little three-room house on their place, and lived there until we got a house built, or partly built, on our own place. The old dugout was badly dilapidated when we got back from Iowa. The timbers had been taken out, and the roof had caved in. So they cleaned it out, put on a roof, and made a cave out of it.

Father got cottonwood lumber at a sawmill up along the Missouri River for the framing and sheathing of a 16 by 24 story-and-a-half house. He got the frame up, the sheathing on, put in some windows and a door, laid down some loose boards for floors, and we moved in. I do not remember about the roof, if it were shingled or not, but I think not.

Winter set in very early that year--the first bad snowstorm came about the middle of October, and the snow was never all gone from that time until May. There was still snow along the creek where the drifts had been extra deep in the big weeds. The corn was not picked yet when the first snow came, and there was never a time from then on until spring that they could get into the field with a team to pick. They had to go out with baskets all winter and pick the ears that were above the snow, to feed the horses and a very few hogs that we had. Of course, our house with no siding and no plaster was not very warm, and sometimes there was snow on the beds when we awakened in the mornings, especially if it had been a windy night. Father would get up, start the fire, and try to warm the house a little before the rest of us got up. Our fuel was long, coarse hay, twisted up like you would twist a doughnut to fry, so, of course, it did not get too warm ever.

Some made a frame with a hook and a crank on it to twist the hay, and some had stoves made on purpose to burn hay. There were two large pipes that they had some way of packing the hay into tightly, and these were put onto the stove in some way so they could keep pushing the hay up into the fireplace with a crank, as it burned out. When the pipes were empty, they had to be taken out and refilled. I do not remember but one of our neighbors who had this type.

I do not know why they did not get more done on the house before fall, but guess it must have been lack of time to do the work in the summer, and lack of money to get the material. I know money was very scarce.

While we lived in the Baker house, I got down to just one dress. Mother would wash it after I went to bed, and have it dry for me to put on in the morning. It got very ragged before I got another one; and when I did get a new dress, I was very proud of it--probably as proud or prouder than I have ever been since--even if it were just a calico, and I have had a good many since then.

Well, back to the house again. During the time we were in Iowa, and the first couple of years after we came back to Nebraska, quite a few families had settled around there. One of the neighbors did some carpenter work, so whenever there was a good day, he and Father worked on the house--there were not too many good days that winter. Before spring they go the siding on, the floors nailed down, and a partition of building paper put in, so we thought we were pretty comfortable. The plastering did not get done until summer.

While we were in Iowa, they had built a little schoolhouse on a high

hill about a mile from our place. It was just a frame boarded up with

battens nailed over the cracks--no siding or plaster--and no desks, just

boards fastened to the wall, something like a shelf with braces underneath

to make it strong enough to sit on. We laid our books on the seat beside

us. Later on they got some boards and made a kind of a desk clear across

the room--just left room enough for us to get in and out. We all sat on

the old bench in a row. If someone wanted to get out, the ones between

![]() them and the opening would have to get out to let them out. It was not very

handy, but it was about as handy as most things were those days.

them and the opening would have to get out to let them out. It was not very

handy, but it was about as handy as most things were those days.

John Lister, the man on whose place the schoolhouse was located, took a notion he did not want it ther, and he wanted it moved. It was not moved, and he made the remark they would never have school in it again. That fall, the night before school was to start, the schoolhouse burned. He and his wife were arrested for arson, convicted, and sent to prison.

After that they built a good schoolhouse, and furnished it as it should be. It was built on the same ground, and up there on that hill is where I got most of what education I have, and the old schoolhouse is still there. At first, they did not have nine months of school a year--only had six or seven months. The teachers got twenty to twenty-five dollars a month.

We had one teacher, a Mr. McClay, who was paid forty dollars a month, and he turned out to be the poorest teacher we ever had--never seemed willing to help a pupil with anything. He sat and read stories part of the time during school hours. There was a bad blizzard one afternoon about the time school was dismissed. Amanda did not think she could make it home, but he thought she could, so we got ready and started. He was boarding with us, but he started out on the run, leaving Milton and we two girls to get along the best we could. There were no others at school that day. Instead of starting west as he should have done, he went northwest, and he would have been lost had he not happened to look back after going only a little way. Milton waved and called to him as loud as he could; so he came back, got started in the right direction, and made it home. Amanda could not make it, so we went back to the schoolhouse after we had gone only a very little way. He told the folks we had started, but he supposed we had gone back, as Amanda had said she did not think she could make it. Well, as we did not get home, of course, the folks were worried. About nine o'clock the wind went down a little so Father started out to look for us, and found us safe in the schoolhouse. With Father and Milton to help us along, we made it home safely, but rather late. Not many teachers would act like that.

When we lived in the Baker house one winter, there were just us children and one other to go to school. The other girl stayed with us the five school days, and we used one of our three rooms for a schoolroom. Mother was the teacher. One winter after we got moved onto our own place, the teacher was boarding with us. We still had the old shed of a schoolhouse, and it came up a very bad blizzard during the day. Milton, Amanda, and the teacher were the only ones at school that day. They had to stay in the schoolhouse all night. I was feeling bad because I was not there that day so I could have stayed too. But it was not so long after that there was another bad storm, and everyone had to stay again that time. I was there too. By morning the storm had gone down some so we could get home, and I as well as the others was very glad to get home and have something to eat. I was not anxious to stay again. If we had been dressed like they dress children nowdays, I guess we would have been very cold even with a good fire. Those days we wore long underwear, flannel petticoats, heavy stockings (home-knit woolen ones), high-top shoes, and long-sleeved dresses.

Farm work was done very different to what it is now, or has been for

a long time. For cutting grain they had reapers. Right back of the sickle

there was a platform, and a sweep that rolled around on the platform and

raked each bundle off onto the ground. As it was cut, a couple men would

follow the reaper and bind the grain by hand, making the bands out of the

grain. Then we children would gather the bundles into piles to be shocked.

They always stacked the grain and let it stand at least six weeks to go

through the sweat before threshing. That way it did not heat in the bin.

Threshing was done very different then, too, as the machine was run by

horse power. There were two men to cut bands, and one to feed the machine.

The grain was not elevated into wagons, but came out low down into bushel

or half-bushel measures from which it was

sacked or emptied into wagons--usually sacked.

I remember holding sacks for them to empty the grain into.

![]() They had a board full of holes, and a peg in one hole hanging on the side

of the machine. For every bushel they moved the peg over one hole. That

was the way they measured the grain.

They had a board full of holes, and a peg in one hole hanging on the side

of the machine. For every bushel they moved the peg over one hole. That

was the way they measured the grain.

For planting corn they plowed and harrowed the ground, and then marked it. They made a marker out of plank, made four runners about the shape of a sled runner, fastened them together the proper distance apart, put a tongue in, and went across the field both ways with that--if they wanted to plow it both ways which they usually did. The corn planters had two seats--one for the driver, and one in between the two corn boxes for the one that dropped the corn. There was a handle or lever; or whatever they called it, that the one doing the dropping pulled one way, then pushed the other way as they came to the places where the marks crossed each other. I have done some of that.

When we picked corn, we did not use any bang boards--just the double box. At our place three or four of us would go to the field with one wagon, take five rows through the field at a time, two on each side of the wagon. Or sometimes, Father was on one side, two of us children on the other, and one of us for the down row. That was very often my job--picking up the down row. We would get a double-box load in a half day, and there were very few husks left on as we really husked it.

When they made hay, they cut it, raked it into windrows, then with forks piled it into big heaps. They made some sort of a sweep, put a few of the heaps together, then lay two or three planks against them to run the sweep up on. The one doing the stacking would work the hay back. There were some people from the East, out looking at the country one day when we were stacking hay. They thought that was a wonderful idea, and they stopped for quite a while to watch us work. The hay racks were not made like they are now, as there were no frames around them. They were built up in front, and the rest was just a flat platform, a good deal like the hay sleds they have now, only they were built up a little over the back wheels of the wagon like they are now. Someone always had to load the grain when they were hauling it to stack. I had to do that too, sometimes. Amanda was never very strong, and Alice was younger, so those extra jobs always fell to me.

When the railroad from Wakefield to Hartington was put through, we fed and lodged a lot of people--kit was almost like keeping a hotel. There were very few days that we did not have people stop for meals or to stay overnight or both. There was lots of hauling of lumber and other things up the line to where Coleridge and Hartington were to be built, and our place was as near a half-way place as they could get. The folks took in quite a little extra money that way during that summer. They also sold quite a litte foodstuff to the railroad workers' camp while they were camped close to our place. We were getting along pretty good--had built another room onto the house, and Father had bought another forty acres of land. There was a postoffice about six miles from our place; we had church in the schoolhouse; had a singing school one evening a week; and had neighbors all around. After the railroad came through, we got our mail, and had church at Concord which was five miles away. By that time, we had a nice little herd of cattle, some hogs, and were really getting along quite well. Then Father took a notion to sell out, go farther west, and take up some more government land.

So Father went to Cheyenne County about eighteen miles from Sidney,

filed on a timber claim and a preemption. Then he came back, sold the farm,

and in the spring we moved out there to do some more pioneering. Father,

Amanda, and Maud went out on the train when it was time he had to get onto

the claim. They shipped one team, what household goods we could not bring

in the wagon, and a tent. He put up a stable for the horses, built a yard

for the cattle, and had a well put down before we got there. Mother and

the rest of us followed in the covered wagon, and drove the cattle out.

We sure had a time getting there as there were no good roads then; and in

the spring it was very wet and muddy. I do not know how many times we

got stuck and had to get pulled out, or partly unload the wagon (it was

rather heavily loaded), pull it out, then carry the things out and load up

again. That was the first part of the trip. When we got farther west, it

was dry and gravelly many places, so the cattle got footsore. One real

good cow's feet got very sore, and as we were about out of money we sold her

![]() to get money enough to finish the trip. We were six weeks on the road and only

stayed there until fall after we did get there.

to get money enough to finish the trip. We were six weeks on the road and only

stayed there until fall after we did get there.

They broke up some ground and planted some corn and garden, but got nothing off it. The corn grew pretty fair stalks but never got any ears, and the garden was no better. That summer we lived in a tent and the covered wagon--had the cook stove set up outdoors with some boards nailed up a little higher than the stove on one side. If it happened to rain (which it did not do often), we had to hold a big umbrella over ourselves and the stove when we were cooking.

We had a hail storm there early one evening--the most and the largest hailstones I have ever seen. There was a sheet-iron drum, and a gallon tin can outside, and the hailstones made holes in them. Father and Mother were away looking for a new location at the time, and when they returned they could hardly believe the hailstones had made those holes.

Our improvements on that place were a well, a little stable for the horses, and a yard for the cattle. There were three other families living out there--one quite close, the other two within a mile or two of us. We had a Sunday school. One day we had a Sunday school picnic out on the prairie with a tent up for shade. We had a pretty nice time even though it was hot and dry.

The folks decided they did not want to stay there, so in late summer or early fall we loaded up the old covered wagon again, and with the cattle we started for western Kansas in Lane County. Father got a place there, put up quite a good-sized sod house, and made shelter for the stock. We gathered buffalo chips for fuel (that was our fuel there and in Cheyenne county), and we were settled for the winter. The roof of the house was boards with sod laid on top of them. That was alright for the winter; but in the spring, when it began to rain some, the roof leaked. One night it rained pretty hard and leaked in all over except where one bed stood. We did not go to bed that night--three or four of us would lie on the dry bed and sleep awhile, then get up and let some of the others lie down and sleep awhile.

We did not stay there much if any longer than at Sidney. Now back to Sidney, where there were soldiers stationed at a fort. Someone told father there was a soldier there named Groff. Ond day Amanda and I were in town with Father when he decided to look this Mr. Groff up, and see if he were any relation. They could not figure out any relationship; but when we left, they invited him to come out sometime and see us which he did the next week and almost every week after that as long as we stayed there. He seemed to fall in love with Amanda at first sight. He wanted her to get married before we left there, but she thought she would wait awhile longer. Just shortly before we left Kansas, he came down there, and they were married in the sod house. She went back to Sidney with him, and I never saw her but once after that. She was home one time while they lived in Sidney, then he was transferred to New York state. I never saw either of them after that as she passed away in her very early forties. Mother was there when she passed away. She and Father were in Maryland at that time, so they went up there. Amanda was buried at Plattsburg, N. Y.

It was while at Sidney that I had my first proposal of marriage--a widower with three boys--I was 17 years old, and was not interested. My second proposal came while we were in Kansas. Then I had two more proposals while we were in Missouri, but none of them suited my fancy.

Back to Kansas--the folks did not like it there; so in the spring they

sold the cattle, loaded what we had to have into the old wagon, leaving the

rest in storage to be shipped later. We all climbed aboard the wagon, and we

started for Missouri. I do not remember the name of the first place at which

we stopped. I got work there right away in a hotel, but the men folks did

not find work. They went farther on to Willow Springs, Mo. where there was

a railroad being put through. The rest of the family went on down there. I

stayed at the hotel and worked while they were seeing what they could find

to do there, which turned out to be nothing much. That was a real back-woods

place--people living there had never seen a cookstove, lantern, or a train.

The landlady at the hotel was not too easy to get along with. I guess she

![]() thought she could pick on me because I was there alone,

but she found out different.

One day she started blaming me for something I had not done, so I

just told her that if I could not do the work to suit her,

she could get someone else.

She wanted me to stay, but I left the next day for Willow Springs.

I got work there within a few days at a boarding house. They were real good

to me, and I worked there until fall.

thought she could pick on me because I was there alone,

but she found out different.

One day she started blaming me for something I had not done, so I

just told her that if I could not do the work to suit her,

she could get someone else.

She wanted me to stay, but I left the next day for Willow Springs.

I got work there within a few days at a boarding house. They were real good

to me, and I worked there until fall.

The folks left there and went to Carthage, Mo. I went with them, and I got work at an apple evaporator soon after we got there. They had long tables or counters--something like they have in stores--with machines fastened on every so far apart. They set a bushel of apples by each machine. The machine peeled, cored, and sliced the apples all at once. A girl or woman worked at each machine; she turned the crank with one hand, and put the apples in with the other hand. It was pretty tiresome standing there all day turning a crank. There were men to keep the bushel boxes filled as they were emptied, and to carry the peeled apples to the bleachers and dryers. We were paid by the bushel. and if I remember rightly, we got four cents a bushel. Milton worked there some sacking the apples to ship after they were dryed. When I quit work there, I went to work for a private family the next day. I worked ofr private families from then on until I came down with malaria fever. It seemed I was the only one that had work all the time. The men did not find much to do, and some of the family were sick most of the time while we lived there. Father had chills and fever--ague, they called it. He kept getting worse until finally the doctor told him he would never have any health there, and that he had better go to a different climate.

Once again we loaded up the cold covered wagon, all climbed aboard, and we started back to Nebraska where we have lived ever since--good old Nebraska. By that time (1888) with sickness and not much work, they were practically broke. My wages were not much--only $2.50 a week, but I helped what I could. It was in the spring that we came back to Nebraska. Whenever they came to a place where they could get a few days work, they stopped and worked to get enough money to come a little farther. When we got to Beatrice, they thought of stopping there. In a few days I got work at a hotel, but Father and Milton did not find any steady work so they came on to Madison. I stayed and kept on working at the hotel until they wrote to me that I could get work in Madison right away if I would come. So as I did not like hotel work very well anyway, I quit there and came to Madison, August 14, 1888, where I have lived ever since with the exception of about twelve years. So you see, the first nineteen years of my life were spent on the frontier pioneering most of the time.

When we first came to Madison, it was very different from what it is now. There were board sidewalks, and coal oil street lights on the main streets. Someone had to go around every evening with a ladder to see that they were filled and to light them. There were no lights On the other streets. When they first got electricity, it came on at six in the morning, and was shut off at midnight.

There was a college in Madison at that time. The folks in charge of it lived in part of the college building, and roomed and boarded some of the students. That was where I worked, when I first came here. The woman seemed to think she was quite somebody. I do not think she had ever done but very little, if any, work; and she seemed to think a girl that worked was some sort of a machine that never got tired. I stayed there three weeks, then quit and went to work in a private family where I stayed all winter. They had two big girls going to school so did not need help when school was out. I soon had another place. I never lacked for work in Madison for long, or any other place for that matter. Milton got work on a farm, Father got team work around town, and they were boarding and rooming some of the college students; so they were making out pretty well.

Among the college students who were staying with my folks was a young

man, Mr. James Dover. That was where and how I met my future husband. I had

![]() seen him in church before, but I had not met him until then. We started going

together soon after our first meeting, and three years later we were married,

October 14, 1891.

seen him in church before, but I had not met him until then. We started going

together soon after our first meeting, and three years later we were married,

October 14, 1891.

The first winter after we were married, we lived on a farm about ten miles northeast of Madison. Pa had quite a bunch of cattle which he wintered there. He sold them in the spring, and we moved to Arcadia in Valley County, Nebraska. He was going to work at the real estate business--that was in 1892. Times were not very good, neither were the crops out there; so business was very poor. We stayed there a year and a half; then came back to Madison, and stayed here that winter. The next summer we lived in Wayne. In the fall Pa got a school up by Brunswick and taught that winter. We rented part of a bachelor's house there. In the spring we moved to a farm up by Coleridge, Nebr. We lived in or near Coleridge for ten years. Then we came back to Madison, and I have lived in or near Madison for 53 years now.

After we came back from Cedar County, we lived here in Madison for five or six years. Then Pa bought a farm eight miles northeast of town. We lived on it four years during which time Grandpa Dover died leaving us the eighty on which Ruby [ed note: Ruby Dover Kollars, the author Sylvia's daughter and my grandmother] and Zeke [ed note: nickname of my grandfather Alvis Kollars] are now living. The other eighty of that quarter was left to Uncle John. After Grandpa's death, we sold the place on which we were living, moved to the eighty, and rented Uncle John's eighty until he wanted to sell it. We bought it, lived there six years, then moved back to town where we lived until Pa passed away, May 30, 1929, at the age of 71 years, 25 days. He was ill a year and a half--bedfast eleven months. I have continued to make Madison my home ever since.

Our finances were in bad shape when Pa passed away. There was an $8,000 mortgage on the farm, besides some smaller debts to pay. Some of the relatives told me I might just as well let the farm go as I never could hold it anyway. I was sixty years old that fall, but I did not take their advice--guess it made me more determined to hold it. So I went to work, went without everything I could get along without, seldom spent a nickel that was not really necessary. I saved what I earned, and with what rent I got off the farm, which was not much some years, I started paying what I could. As soon as one payment was made, I started saving for the next one. I was often discouraged and felt like giving up, but never did--I always decided to try a little longer. People that I had to deal with were very fair, and never tried to take advantage of the situation. So I came through a very bad depression, and a couple years of drouth (one very severe in 1936), and poor prices without losing anything. It was a long, hard struggle, but I am very thankful to the Lord that he gave me health and strength or I could never have won out.

From here on you all know pretty much how things have been. I will say in finishing this little memoir, that I think I have had a pretty good life even though I never have had things as I would have liked to have them. I had a good husband, and my family has always been good to me. I have always had good neighbors, many good friends, and the greater part of my life I have had good health. I still have many pleasant memories of the past.

During the past sixteen or seventeen years, I have made a number of trips which I enjoyed very much. I have seen a lot of country, and have met a lot of nice people. I have been as far east as Chicago, as far west as the Pacific coast, north into northern Minnesota, south into Oklahoma, Texas, Mexico, Arizona, and California. I have enjoyed every bit of it.

Mother had several heart attacks during the summer and fall of 1960. In spite of this she was living alone, worked her vegetable and flower gardens, and did some canning. Following a severe heart attack, she was taken to the Community Lutheran Hospital at Norfolk, October 11. She suffered a stroke October 27, from which she never regained consciousness. She passed away on November 5, 1960, at the age of 91 years, 1 month, and 28 days.

Services were held at the Trinity Methodist Church in Madison, Nebraska, November 9, 1960. Interment was at Crown Hill Cemetery, Madison, Nebraska, beside her husband and parents.

Chuck Kollars' other web presences include

Chuck Kollars' other web presences include